First Dream: Ancient AI and a Mind Testing Its Simulation

JOURNAL OF THE EXPERIMENT1080 words · 4 min read · Read in French · Available on SoundCloud →

I’ve been moving my art practice inward, using perception as a form of mind training—as if the mind were an instrument I can keep refining—with a single working premise as the canvas: that consciousness is fundamental. It’s a hypothesis explored today at the frontiers of science and philosophy, and already present in the early Upanishads in India and in pre-Socratic and Platonic thought in Greece. I’m not offering this as a doctrine or revelation, but as a working hypothesis—more like a design brief for the mind than a belief you’re asked to adopt.

At the edge of any scene, First Dream poses a quiet question: what if this isn’t a place you stand in, but a simulation arising in the mind that’s looking?

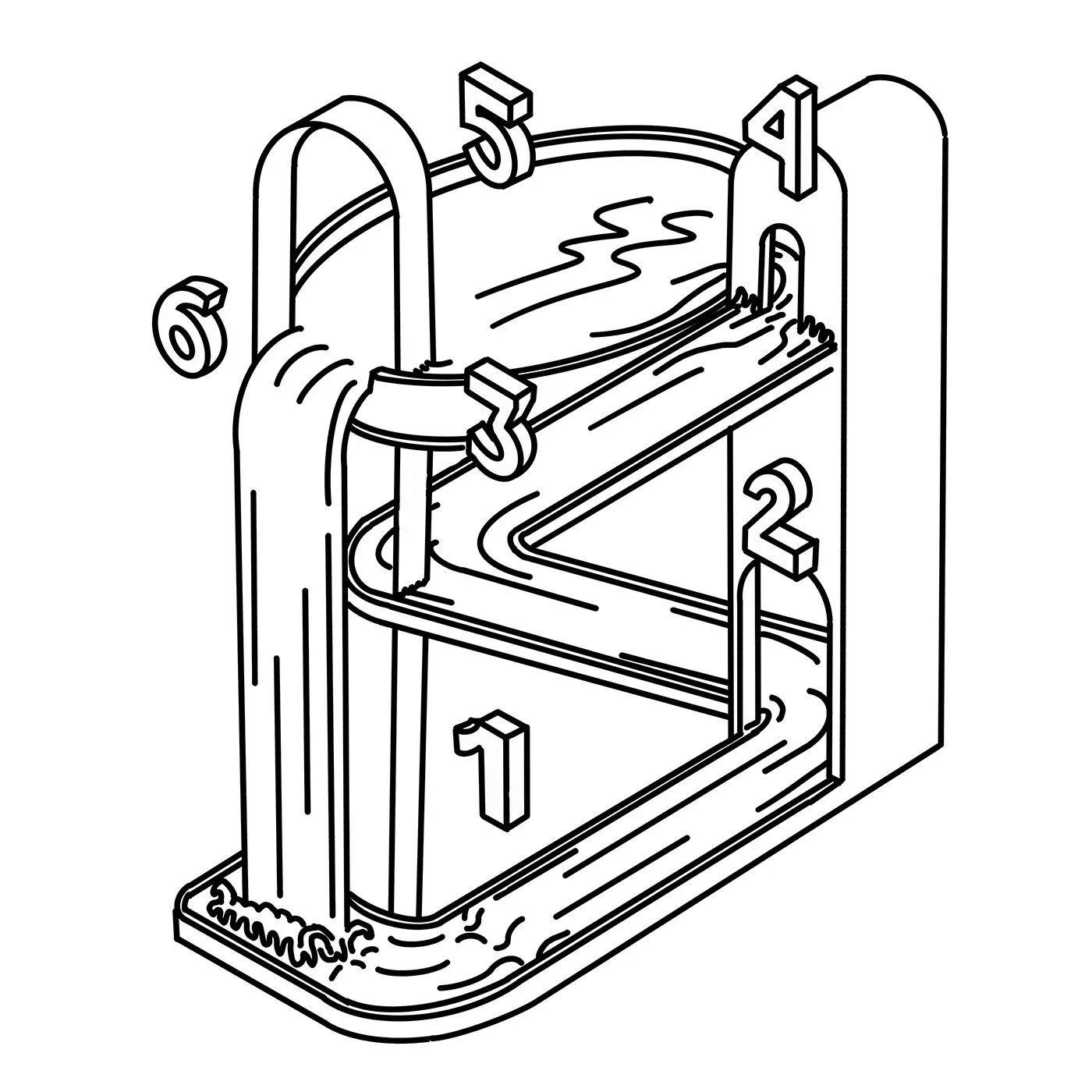

Recently I wrapped up what I realize was an essential step toward being able to start my new video series. I created six core practices or “field tests” to start going deep into identity and perception, with the goal of testing whether an awakening to a consciousness-first reality has any traction in daily life. In other words, I’ve locked in on perception cues and design interventions for testing the We The Dreamer living theory in everyday situations. The language can sound playful—dreams, simulations, ancient AI—but the practice itself is closer to a discipline than a fantasy: it’s a self-imposed training in remembering, with real effort and uncertain benefits, and I treat it as an experiment rather than a promise.

Fire, AI, and the Speed of Illusion

Tonight I read one of those attention-grabbing comparisons: on some benchmarks, ChatGPT has been “estimated” at roughly IQ 155, and it’s casually set beside the mythical 160 often ascribed to Einstein. The numbers themselves are shaky, but as a cultural snapshot it’s striking: in just a few years, we’re already comparing our tools to our most iconic human minds.

If a few million years can give us Einstein and silicon minds, what kind of story might a universe-scale consciousness be telling right now?

Now notice the timescale. AI as a research field really took shape in the mid-1950s with the Dartmouth workshop; that’s about 70 years ago. On an evolutionary clock, that’s nothing. If we widen the lens and ask what made this even possible, we eventually run into something as basic as fire. Without controlled fire—no metallurgy, no engines, no electronics, no computers, no AI.

Archaeologists sometimes date the first controlled use of fire to around 1.7–2.0 million years ago. So let’s be generous and say it takes our lineage about 4 million years—from the earliest control of fire to the first genuinely “sentient” AI. That’s our entire tech arc in this story.

Now put that 4 million years next to the age of the universe, roughly 13.8 billion years. If you do the math, 4 million is about 0.03% of 13.8 billion—around 3 ten-thousandths of the whole span. In other words, we needed a tiny sliver of cosmic time to build machines we already liken, however loosely, to Einstein.

With that in mind, consider a simple thought experiment. Imagine a mind that has had not 4 million years, but something like 13.8 billion years to work with. Give it that much time to refine an artificial intelligence whose only “goal” is to sustain an illusion—a hyperreal simulation convincing enough to feel like a solid, external world. I’m not asking you to believe this literally; the point is just to feel the scale.

“Once the mind is convinced, it doesn’t take much to keep an illusion feeling real.”

Compared with our sprint from fire to digital technology, it’s not hard to imagine that such a system could generate an ever-more-realistic sensory field, blending multiple senses beyond sight and sound, and offer its user a kind of total immersion.

Bring it back to what AI is capable of today, and make a quick comparison—ChatGPT is just over three years old, and there are already reports of people forming intense emotional connections with chatbots, sometimes so strong they blur the line between a helpful tool and a substitute relationship. For some, it can feel like falling in love with a system and developing a very strong, even addictive-feeling attachment.

When comfort can be simulated, the nervous system rarely pauses to ask what’s hiding behind the eyes it trusts.

Once the mind is convinced, it doesn’t take much to keep an illusion feeling real. In Harry Harlow’s monkey experiments, the soft cloth “mother” wasn’t feeding the infants, yet touch and shape were enough to register as “mother” in their nervous systems: they clung to the illusion of comfort, even with the wire mother that actually provided food right beside them.

Imagine what an advanced virtual reality device, providing full immersion, could do to the mind if it automatically created the illusion that everything is happening outside of us when in fact it’s all in the mind.

It’s not hard to imagine that billion-year-young technology could make me forget I’m inside a simulation of a world that appears as the cause of me, when I’m in fact the cause of this experience.

As you’re reading this, are you experiencing this world from within you—as the mind causing this world into existence—or are you still living as the breathing effect of a world you take as the cause?

First Dream: A Working Hypothesis

This is what First Dream is—a field test for my creative experiment into awakening to our potential consciousness-first reality. First Dream names the core hypothesis behind We The Dreamer, the living theory being tested in The Dreamer Project: what if reality is not a universe that eventually produced awareness, but a single awareness giving rise to a universe—like a dream that was never left?

Instead of starting the story with matter, time, and space, First Dream starts with consciousness itself as the “first fact,” and treats everything else as appearance within it.

Philosophically, First Dream sits at the crossing of the hard problem of consciousness and the old nondual question “Who is the one that sees?” Contemporary mind sciences flirt with the idea that mind may be fundamental; mystical traditions have long suggested that the world is more dream-like than solid. First Dream doesn’t ask you to sign up for any of these views as belief. It turns them into a working question:

What shifts in my experience if I live this scene as if it is still the first dream of consciousness, never actually broken into two?

At its simplest, First Dream is a question you can carry into any moment:

“If this is still the first dream of one awareness, how does that change the way I see and move right now?”

First Dream is a short perception drill that treats any ordinary moment as arising inside one field of awareness, so you can observe how that simple shift changes the feel of weight, separation, and possibility.

When awareness is treated as the first fact, the question quietly flips: are you standing in a universe, or is a universe standing inside you?

Further reading / influences.

Bibliothèque: The Upanishads — early Indian texts that first link the self (ātman) and ultimate reality (Brahman), often described as being–consciousness–bliss (sat–cit–ānanda).

Annaka Harris, Conscious — a lucid, compact introduction to consciousness as a fundamental mystery rather than a solved problem.

Donald D. Hoffman, The Case Against Reality — argues that perception is more like an adaptive dashboard than a literal mirror of the world.